EMBO, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, eLife/Sciety, and the Knowledge Futures Group have recently launched a collaborative pilot project called DocMaps. The project’s goal is to create a common framework that will allow the machine-readable tracking of the peer reviews of individual preprints.

If you’ve lived in an old house, you are probably familiar with the mysteries of plumbing. Where are the pipes? What kind of pipes are they? Can they easily be connected to a modern sewage system, or are you stuck with a septic tank? Plumbing may be a boring topic to most, but it’s hard to imagine modern life without it (reading descriptions of courtiers relieving themselves under the marble staircases at Versailles may give you an idea of what it was like in even the most opulent of circumstances).

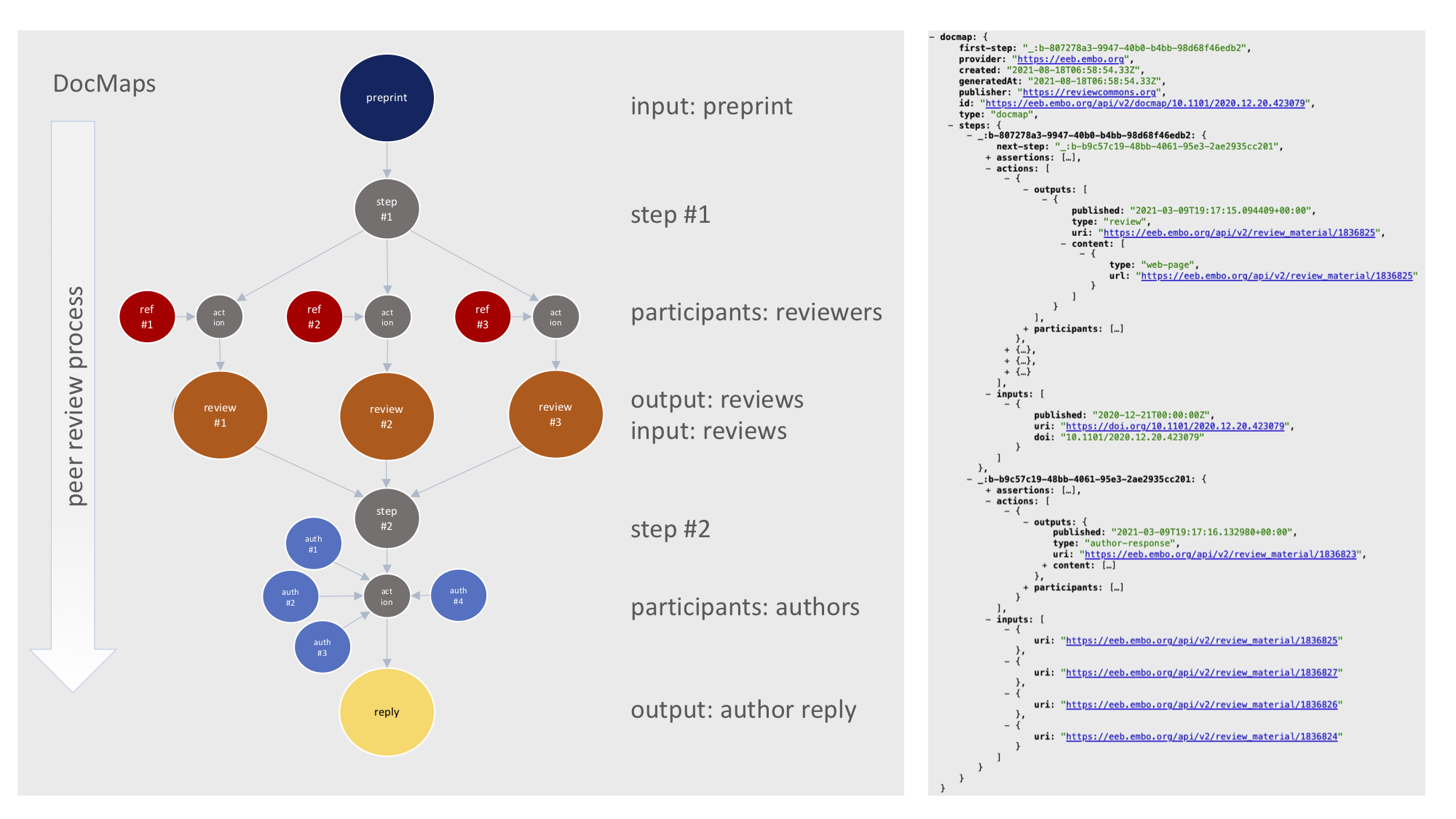

EMBO, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), eLife/Sciety, and the Knowledge Futures Group have recently launched a collaborative pilot project called DocMaps. The project’s goal is to create a common framework that will allow the machine-readable tracking of the peer reviews of individual preprints. It may sound unglamorous – as Review Commons project leader Thomas Lemberger puts it, “there is really nothing to see on the surface, this is the plumbing behind publishing” – but DocMaps could represent a major improvement to the preprint infrastructure, allowing users to follow the evaluation process over time.

A common standard for information exchange

“Currently there is no common standard to exchange information about the peer review process. We produce all these peer reviews, we publish them and we move them around from Review Commons to BioRxiv or to publishers, from publishers to Review Commons, and so forth. This involves more than just the review content, there is also the metadata around the review process,” says Lemberger. “How many reviews were collected? Were they all organized by the same journal or the same platform? What paper does it relate to? Who was in charge of that process? Was it spontaneous, or was there an editorial team?” DocMaps will attempt to provide a machine-readable answer to all these questions. As BioRxiv co-founder Richard Sever summarizes it: “The idea of DocMaps is to create something that tells you about the provenance of the document that you’re looking at.”

The idea of DocMaps is to create something that tells you about the provenance of the document that you’re looking at.

Richard Sever, co-founder of bioRxiv

“We know that there are going to be many peer reviews of BioRxiv papers,” said Sever, “but because of the decoupling of dissemination from peer review at BioRxiv, you see each peer review but you don’t know anything about it.” DocMaps will provide detailed information on the provenance of reviews, including links that explain how different platforms and publishers organize their review process. “The DocMap will tell us that this review came from Review Commons. It will provide a link where you can find out what Review Commons is and what their peer-review process involves,” said Sever.

DocMaps will also inform users if the peer review process was linked to any kind of evaluation or decision step – for example, an editorial decision to publish the manuscript. The review process does not end with the reviewer comments, and outcomes are not limited to publication decisions. “Did the authors reply? If so, can I find these replies? There is (currently) no way to document in a machine-readable way this series of steps,” says Thomas Lemberger. Ultimately, the DocMap should be an updatable case file of a manuscript’s peer review process.

Stepping away from monopolies in publishing

Much of the current infrastructure of scientific publishing is provided by commercial services using proprietary technology. Implementing changes in manuscript processing software even within a single academic press can be a difficult and expensive proposition. Connecting information about the preprint and publishing process across different publishers and platforms is a laborious, manually curated process that would charitably be described as “byzantine”. The DocMaps project has kicked off at the nascent stage of preprint peer review. It’s an attempt to install an open-source infrastructure that is managed by the academic community, instead of reverse-engineering transparent and open science principles into pre-existing commercial publishing technologies. “It’s the kind of improvement that gets us out of this ditch where everything is monopolized by very few mega-publishers,” says Lemberger. “We would like to reclaim the infrastructure of publishing for the scientific community.”

We would like to reclaim the infrastructure of publishing for the scientific community.

Thomas Lemberger, Review Commons project leader

Authors are often supportive of open science initiatives but are understandably cautious about improvements that add to their workload, so it is important to point out that the DocMaps project puts all the workload on the professional plumbers. All the required metadata will be uploaded by the managers of the different platforms.

DocMaps is a pilot project and it’s fair to ask: what will success look like? Lemberger and Sever both give the same answer: growth – with third-party peer review platforms and other publishers adopting the DocMaps framework. “Adoption. I think that’s what success looks like for DocMaps, that people like the plumbing and decide to build it into the broader ecosystem,” said Sever.